In 1990, American shopping malls reached their apogee: A dizzying 19 malls opened within the year. These million-square-foot indoor retail centers provided entertainment, food, and, above all else, the thrill of seemingly endless choices—an insatiable consumer’s dream. Suburban neighborhoods became bona fide destinations, thanks to the fluorescent glow of the mall.

Three short years later, Delia’s, a fashion brand targeting preteen to college-aged women, hit the market. Its success was bright and instant, like a white hot firecracker. Founded by Stephen Kahn and Christopher Edgar, former college roommates who set up shop in New York City’s West Village, Delia’s was an exception to the frenzied pace of mall-based retail, diverging completely from the era’s other popular clothing brands—because it had no brick-and-mortar stores to rely on.

There was nothing else like it at that time.”

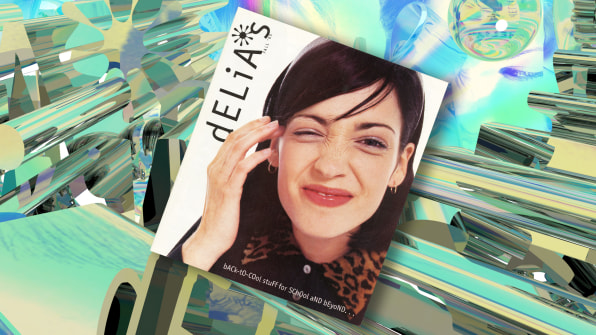

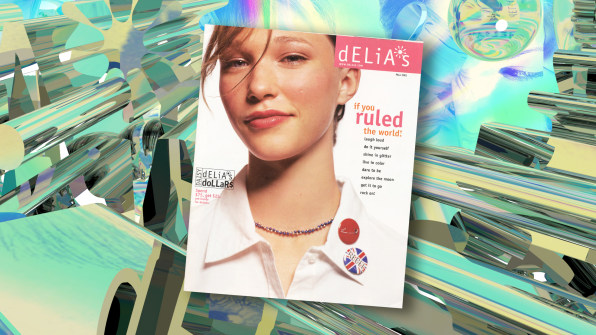

Today, that’s not unusual—e-commerce has borne a new generation of direct-to-consumer brands that have no retail footprint. But that future was still decades away. Delia’s launched in a firmly pre-internet era, developing an unlikely following through mail-order catalogs that featured novel design and messages about individuality and sisterhood. The company’s near-instant success was thanks to its editorialized approach: In a 1997 Los Angeles Times article, CFO Evan Guillemin claimed that Delia’s had convinced its private investors of its unusual “magalog” business model (a combination of “magazine” and “catalog”) by comparing it to MTV. “We told them to think of us as a ‘channel’ through which you can program different types of apparel brands,” Guillemin said. “We, like MTV, stay constant . . . but we’ll provide them with a constantly changing assortment of designs and brands.”

For a time, Delia’s was the voice of popular fashion, speaking in a way no heritage mall brand ever had. “It was the very start of the girl power movement, especially for that younger generation . . . at that time, there was no one else speaking to that group of kids, especially [a clothing brand] being sent directly to their home in catalog form where they could kind of express themselves and see themselves, and not just what they’d be seeing at the mall,” says Jim Trzaska, a photo producer who also assisted with buying and merchandising at Delia’s, who was hired during the brand’s infancy in the mid-’90s. “Delia’s put a spin on things that was a little more individualized and counter-culture, if you will. That’s why it was so successful back then, because there was nothing else like it at that time.”

The catalog format, more magazine than store, let Delia’s sell a lifestyle as well as products. In this sense, Delia’s foreshadowed the direct-to-consumer fashion revolution, where small startups target specific demographics with editorial content and media as much as traditional advertising. If the Delia’s girl was in high school today, she would no doubt be an influencer, selling a drool-worthy lifestyle very few can attain. Delia’s promised to help you look like the girls its catalogs promoted. All you had to do was dial 1-800-DELIA-NY.

Designing Delia’s

In the years leading up to the new millennium, most American teens had only a few ways to access fashion: They could spend hours at the mall, or be relegated to borrowing hand-me-downs or shopping in each other’s closets. When Delia’s first started out, founders Kahn and Edgar were marketing to college-aged women. But they decided to pivot when they realized they could make more money catering to this younger crowd all across the country. Through Delia’s, small-town and suburban girls would have the opportunity to dress like they lived in a major cosmopolitan city. Thanks to strategically placed advertisements in teen magazines, the demand for Delia’s catalogs grew. At its peak, 55 million copies were sent out to girls across the country every year.

This analog era, before the advent of the personal home computer, let teens find inspiration in print form. “Delia’s sending the catalogs to their mailbox [allowed girls to] get together with their friends after school, and circle things . . . they read the catalog like a magazine. I think that physical part of being able to have it at home and have parties around it and tear things out and put it in your locker was something so new for this age group, it just took off,” says Trzaska. Each issue of the hybrid mail-order catalog magazine, which came out roughly 10 to 12 times per year, existed as an intelligent form of direct-to-consumer marketing. The Delia’s look was playfully irreverent and quirky. The forward-thinking brand identity, right on time for the new decade to come, epitomized young girlhood in the ’90s: casual, creative, and a little bit awkward with puberty and possibility.

All the other publications geared at this market were all about, like, ‘how to kiss a boy.’”

The models, who were often scouted on the street, were “real” girls with personality, and stylists dressed them in crew-neck crop tops and baggy jeans and violet-colored mini dresses in equal measure, a prescient nod to the gender-neutral fashion world we know today. The brand’s target audience—young women ages 10 through 24—were at the stage in life where they were beginning to find their voice, and Delia’s helped amplify it. The price point for its products—bottle cap belts, platform Mary Janes, metallic eyeshadow, bedazzled cardigans—were within reach for girls getting the catalog delivered to their (predominantly) middle-income households. “It was comparable to what you would find in your mall store, it wasn’t luxury pricing,” Trzaska says.

Charlene Benson, the creative director of photography, was responsible for the brand’s widely replicated design style. In her role, she worked with photographers, stylists, art directors, and casting agencies to create the universe of cool that would define this generation’s transition from the late ’90s into the year 2000.

“In the beginning, a lot of [the design choices] were about timeline and budget. But for the most part, the first people that worked on [the catalog] just wanted something really simple,” Benson says. “I loved figures on white, and I was working at Mademoiselle at the time, so I wanted to do something that didn’t quite look like what we were doing at Mademoiselle. I think a lot of the personality came out of the clothes and the personality of the models.”

Cool girls, magazine cred, and the death of regional fashion

Delia’s had a very female-forward creative team—rare, at the time—and it undoubtedly was a factor in the brand’s success among female consumers. “What was really remarkable was that the buyers were all like our customers— young girls right out of college and sometimes still in college, and they kind of looked and dressed like our customers,” Trzaska says. “I think that was another reason Delia’s struck a chord . . . even though the founders were two guys, they were smart enough to build a team that reflected the customers. They had the foresight in the ’90s to hire women and girls that were like the customers they were trying to reach.” The “cool girl” aesthetic oozing from the catalogs was encouraged by a team of creatives who liked things a little messy.

“It was a little post-punk,” Benson says. “It was the way people were dressing in New York. Also, the brands that we carried, some of them were little brands happening in New York or Los Angeles, and we made it possible for them to sell nationally. It used to be like the kids in New England wore their jeans a certain way, [but this was] everything, everywhere. I think Delia’s was the beginning of the death of regionalism.”

I think Delia’s was the beginning of the death of regionalism.”

In a sense, this is true: The catalogs, which were delivered to addresses across the country, introduced broad swathes of the country to budding Y2K-era trends. “What I found was that young women would use the book itself as a sales tool to sell their parents [on the clothing] by showing them a picture,” Benson says. “The parents can see it and approve it and understand it and, in context, kind of celebrate the creativity and friendship and the kookiness of these girls. All the other publications geared at this market were all about, like, ‘how to kiss a boy.’ And we wanted to leave that narrative out of the picture and just kind of [focus on] them and their style.”

Benson remembers the Delia’s team shooting 60 days a year for the catalog; she often directed the photographers to shoot “a lot of film” to capture the young models’ organic expressions. Sometimes, photographers used fish-eye cameras to magnify certain parts of the models’ outfits or emphasize the in-your-face nature of the Delia’s aesthetic. The visual language of the catalogs was clean—all images were shot on a stark white background—yet collaged; models appeared as floating, almost photoshopped figures across the spreads in non-linear layouts. Benson’s background as a designer at various magazines was great preparation for her early role at Delia’s, and also drove her to imagine new approaches to design that felt fresh and original.

“I was always working on an upright rectangle, so the opportunity to work in a square setup kind of shook things up in this wonderful way,” she says. “When you’re working on a certain shaped page for a certain time it was really freeing.”

The catalogs also featured bonus offer giveaways (“FREE super hot cd WiTh oRders over $75”) and surprise gifts. It also asked customers to talk back and communicate with the brand, an entirely novel concept. “Very early on, we were always creating things to drop in the packages, and we made a little postcard where girls could put a picture of themselves to show us who they were,” Benson remembers. “We got hundreds and hundreds of photos, and it was really the beginning of what we see now where people can’t stop taking pictures all the time. It got them in the conversation, so then we became in conversation with them.”

It was really the beginning of what we see now where people can’t stop taking pictures all the time.”

The mail-order publication also included witty, seemingly unrelated copy, written in a voice fit for a fun-loving teen. “I didn’t want the copy to repeat and say what the person was already saying; I thought of it as an opportunity to have this parallel dialogue with the shopping experience,” Benson explains. “And there were a couple styles of typography [so we] could fit a lot on the page but still have it feel fun and wonderful. In the end we just really wanted to have some fun. And the line type going through the page kind of gave it some structure.”

“So much thought went into the lowercase font and the little sayings, every issue would have a theme of what the captions would say,” Trzaska says. “Sometimes they made no sense at all . . . but it [made you wonder] what the voice of Delia’s had to say this season.” Benson’s use of a typeface that was a surprising mix of uppercase and lowercase letters was inspired by a typeface style she’d seen at Sassy magazine, and she decided to not have any letterforms stop at the end of a page to encourage shoppers to keep turning and reading the catalog’s story.

The turn of the millennium was an era sandwiched in between the analog past and an uncertain digital future, and the prevailing aesthetic, with its off-kilter proportions and deep metallics, seemed to wink at the wild and exciting mystery of it all. To Benson, her approach to the catalog—and the brand identity as a whole—came from two influences that coexisted at the time.

“One was the MTV [look] where everything was distressed–every font was distressed and there were all these kinds of backgrounds,” she says. “And another one was more direct and cleaner, the grandmother of what we have now, where the image is more important than typography or design, which I think is what we were kind of doing at Delia’s. Part of that came out of a really tight timeline and our really lean budget on everything we did, so we had to get the most personality with the least number of elements [and] presented it in a unique way.”

Too young for malls, too old for the internet

But much like the mega malls of the 1990s, which met a precipitous decline thanks to the birth of online shopping, so too did the mail-order catalogs of Delia’s.

“The web became a big deal so we started having a website with imagery and stuff, then it moved into e-commerce,” says Trzaska. “What really changed the brand was when they tried to dabble into brick-and-mortar stores. I don’t think they had the infrastructure and it’s very expensive . . . a lot of resources went to that, which kind of hurt the print side as well. They just couldn’t translate the magic of the print to stores.”

When Delia’s was acquired by Alloy Inc. in 2003 for $50 million, the internet and e-commerce was finding its footing. Though Delia’s always had a “Web 1.0” aesthetic, it was difficult for the team to adjust to a changing retail landscape. There was very little precedent or information available on how to build a thriving retail site online.

Twenty years later, Delia’s is notable for the way it predicted the future of retail; a future where brands target consumers directly (now, through their phones) and break the fourth wall to speak directly to fans. Though printed catalogs have largely disappeared, today’s e-commerce powerhouses have adopted many of the marketing tactics Delia’s pioneered, from targeted advertising to consumer-centric lifestyle content. The catalogs—and their smart design and editorial vision—defined the aesthetic of the millennium. It was a powerful visual language that’s still echoing through the fashion world, especially in our current era of nostalgia for its particular brand of late-’90s cool.

“It’s a cyclical fashion thing, it’s the ’90s moment,” Trzaska says, pausing. “But I also think in terms of women’s fashion and girl fashion, we’re also culturally in a time where women are finding their voice again. The last time we saw that was around the ’90s when self expression was more prevalent, then we went through a period where everyone did want to look the same, and now that’s changing again.”