Clinton, himself, will not endorse or campaign for anyone in the primary, his spokesman, Angel Ureña, told me, pointing out that this is standard practice for him in presidential races that haven’t included his wife. He’s been largely benched politically since his wife’s 2016 loss and the onset of the #MeToo movement. An NBC/Wall Street Journal poll this week showed that just 29 percent of Democrats had a “very positive” view of him and 35 percent had a “somewhat positive view of him,” compared with 69 percent who had a “very positive” and 21 percent who had a “somewhat positive” view of Obama.

Read: Did Bill Clinton see this coming?

Not all Clinton alums are on board with Bullock. Jerry Crawford, who ran operations in Iowa for Clinton in 1992 and 1996, is backing Senator Cory Booker of New Jersey, and is also holding on to the Clinton-infused hope that there is still time for the race to be shaken up. Many old Clinton allies are firmly in the corner of the Democratic establishment that is locked on to former Vice President Biden—perhaps most prominently represented by Ed Rendell, the former Pennsylvania governor and DNC chair during Clinton’s tenure. More are scattered across a few other campaigns.

“Were it not for the new debate rules, Bullock would be looked at as a promising candidate who was in fine position to take off in the fall, which is when candidates who win Iowa start to take off,” said Jennifer Palmieri, an aide in the Clinton White House and Hillary Clinton’s 2016 communications director, who has offered advice to Bullock, along with other Democratic candidates. “I think it’s dumb to drop out when those debates have not proven to matter.”

They have mattered in drying up fundraising and other support, as Inslee and Senator Kirsten Gillibrand of New York learned: Both dropped out before summer’s end. Bullock’s campaign spokeswoman, though, told me that with the third-quarter fundraising deadline coming up at the end of the month, the campaign feels it will have the funds necessary to go on.

“I get asked this question a lot, ‘Why am I supporting him?’, and particularly at this point in the game, ‘Why am I still supporting him?’” says Anne Andrew, who’s spent her career in environmental work and was Obama’s first ambassador to Costa Rica. Her husband, Joe Andrew, was a DNC chair during Clinton’s presidency, but she says she sees the electoral argument. “There’s a level of certainty and a level of historic, demonstrated success with Steve,” she said, referring to his wins and record in Montana.

Jimmy Carter came out of nowhere to win the Iowa caucuses in 1976, but he told me in an interview last year that he doubts he could have done that in the current world of massive fundraising. Senator Michael Bennet of Colorado, who’s among those tied with Bullock for not much at all in the polls, but is also running on an argument of not rushing out of the race to satisfy the base, received the endorsement of Gary Hart two weeks ago in New Hampshire. Hart, the former Colorado senator and presidential candidate, wistfully recalled coming from behind and almost toppling a former vice president in the 1984 Democratic primaries.

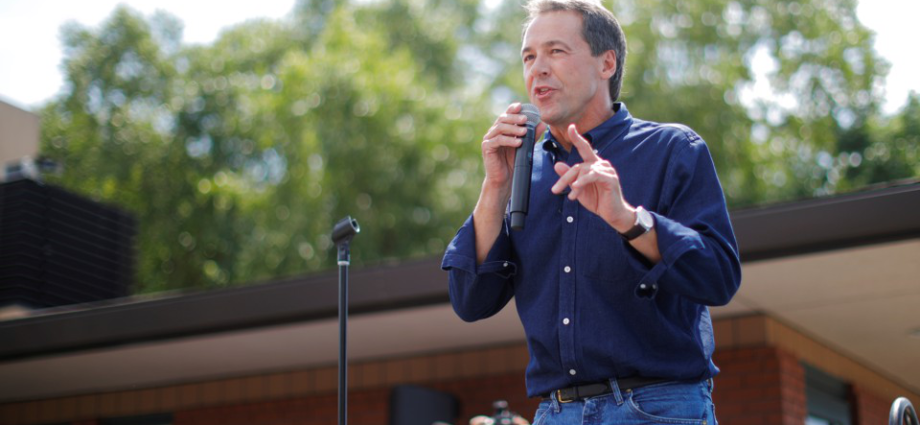

Bullock, trying not to be history himself, is hanging on to history: “At least in the past,” he told me, “there’s been a premium for people that have actually had to run things and make government work.”

This story has been updated to clarify Jennifer Palmieri’s connection to Governor Steve Bullock and other 2020 candidates.

We want to hear what you think about this article. Submit a letter to the editor or write to letters@theatlantic.com.

Edward-Isaac Dovere is a staff writer at

The Atlantic.